Politics

The Struggle for Sovereignty

Iraq’s Path to True Democracy

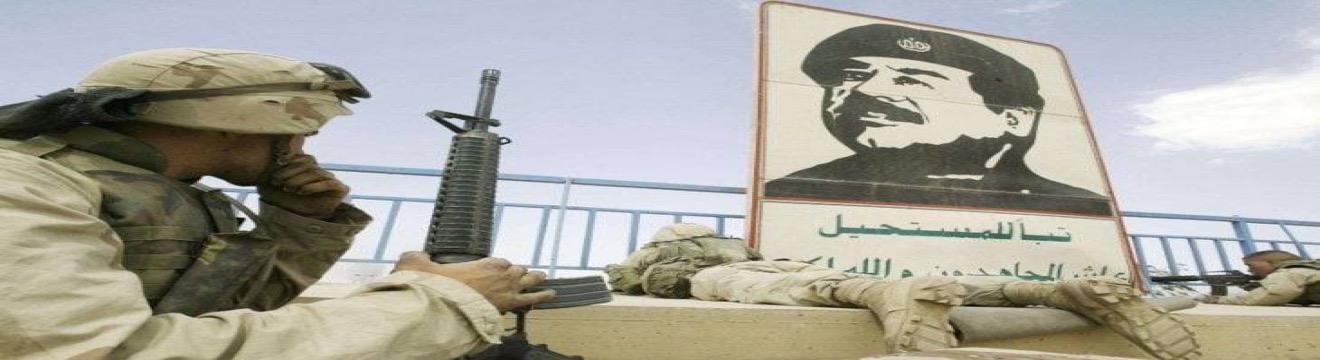

Article cover

In Iraq, the post-2003 experiment with democracy has proven deeply flawed .

The so-called democratic majority was represented not by genuine national figures, but by individuals handpicked and supported by foreign powers. These individuals — politically, socially, and ideologically aligned with external actors, some of whom had fought bitter wars against Iraq — were imposed upon the country without consent or popular legitimacy.

The so-called democratic majority was represented not by genuine national figures, but by individuals handpicked and supported by foreign powers. These individuals — politically, socially, and ideologically aligned with external actors, some of whom had fought bitter wars against Iraq — were imposed upon the country without consent or popular legitimacy.

The process of regime change, conducted through a massive U.S.-led military invasion, culminated not in a national awakening, but in the appointment of a political class that did not reflect the will of the Iraqi people. The supposed liberation became an occupation — not just of territory, but of Iraq’s political future. Those who took power were often loyal to foreign states, including Iran, which has had a two-thousand-year history of rivalry with Iraq. How, then, can Iraqis be expected to believe in a democracy handed to them by foreign occupiers?

The genuine Iraqi elite — scholars, engineers, administrators, and patriots who built Iraq through the 1970s and 1980s — could have led a transition to a stable and just democracy. These were the minds capable of establishing institutions grounded in education, law, and national dignity. Yet instead of being empowered, they were sidelined, targeted, and in many cases, assassinated. They were replaced by unqualified opportunists chosen for their loyalty to external patrons rather than their competence or patriotism.

The genuine Iraqi elite — scholars, engineers, administrators, and patriots who built Iraq through the 1970s and 1980s — could have led a transition to a stable and just democracy. These were the minds capable of establishing institutions grounded in education, law, and national dignity. Yet instead of being empowered, they were sidelined, targeted, and in many cases, assassinated. They were replaced by unqualified opportunists chosen for their loyalty to external patrons rather than their competence or patriotism.

What Iraq needed was what might be called a “democracy of the capable” — a period led by a meritocratic elite that could guide the country out of the ruins of dictatorship and sanctions. Instead, Iraq was pushed into elections while still fractured by war, plagued by illiteracy, and burdened with a society exhausted by decades of authoritarianism and economic collapse.

Today’s Iraq is a patchwork of power centers: over 35 militias operate freely; two armies — one Arab, the other Kurdish — function within a single state; foreign militaries from Turkey and Iran occupy parts of the country; and remnants of terrorist organizations like al-Qaeda and ISIS still threaten security. Drug trafficking flourishes, and vast oil fields are under the control of private families and militia leaders. Meanwhile, millions of Iraqis live in poverty, children sleep on the streets, and entire neighborhoods are governed not by the state, but by gangs.

Today’s Iraq is a patchwork of power centers: over 35 militias operate freely; two armies — one Arab, the other Kurdish — function within a single state; foreign militaries from Turkey and Iran occupy parts of the country; and remnants of terrorist organizations like al-Qaeda and ISIS still threaten security. Drug trafficking flourishes, and vast oil fields are under the control of private families and militia leaders. Meanwhile, millions of Iraqis live in poverty, children sleep on the streets, and entire neighborhoods are governed not by the state, but by gangs.

So where is this democracy we were promised?

According to UN statistics, Iraq has more than 17 million people who are illiterate — unable to read or write. Add to that around 7 million recently naturalized individuals from unstable regions such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. How can democracy function under these conditions? How can elections be free when weapons are in the hands of tribal leaders and armed factions?

There must be a flaw — either in the concept of democracy as imposed on Iraq, or in its catastrophic application.

According to UN statistics, Iraq has more than 17 million people who are illiterate — unable to read or write. Add to that around 7 million recently naturalized individuals from unstable regions such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. How can democracy function under these conditions? How can elections be free when weapons are in the hands of tribal leaders and armed factions?

There must be a flaw — either in the concept of democracy as imposed on Iraq, or in its catastrophic application.

Who is responsible? Is it only America? What about the Arab states that supported the war and the post-war political structure? And what of the Iraqi people themselves? How can a people choose their future when they have been deliberately disempowered?

It must be said: genuine democracy cannot thrive in Iraq as long as militias, not the state, dominate the political scene. The United States, if it truly seeks to support democracy in Iraq, must begin by helping dismantle these armed factions. Only then can Iraq begin to rebuild a system of law and governance based on justice and national interest — not factional loyalty or foreign dictates.

It must be said: genuine democracy cannot thrive in Iraq as long as militias, not the state, dominate the political scene. The United States, if it truly seeks to support democracy in Iraq, must begin by helping dismantle these armed factions. Only then can Iraq begin to rebuild a system of law and governance based on justice and national interest — not factional loyalty or foreign dictates.

Beyond morality and democratic ideals, there is also strategic logic: a stable, sovereign, and democratic Iraq would not only serve its own people — it would also serve American interests. A strong Iraq could become a reliable partner and a stabilizing force in the Middle East, strengthening America’s regional position. More than that, Iraq can serve as a secure geopolitical bridge toward the Far East — a critical pathway through which the U.S. could extend influence and access near current and emerging rivals such as China. A democratic Iraq, aligned with Western interests, could be America’s most vital platform in the heart of Eurasia.

In today’s global order, there is no room for neutrality. Iraq must define its foreign policy clearly. Will it align with the West or the East? More importantly, do Iraqis even know where they stand — and do they have a political compass to guide them toward sovereignty, stability, and true democracy?

Or an ambiguous path to armed struggle or a new revolution !

In today’s global order, there is no room for neutrality. Iraq must define its foreign policy clearly. Will it align with the West or the East? More importantly, do Iraqis even know where they stand — and do they have a political compass to guide them toward sovereignty, stability, and true democracy?

Or an ambiguous path to armed struggle or a new revolution !

Liability for this article lies with the author, who also holds the copyright. Editorial content from USPA may be quoted on other websites as long as the quote comprises no more than 5% of the entire text, is marked as such and the source is named (via hyperlink).